Gen Z's Defining Years: What they *really* are, and why no one agrees

Look, I gotta be honest, when I first heard about Labubu dolls, my eyes just about rolled out of my head. Another "ugly-cute" collectible, another celebrity endorsement, another marketing blitz for some piece of plastic. But then you dig a little deeper, past the shiny PR, and you realize it ain't just about a toy. This whole Labubu thing, the Pop Mart phenomenon, it’s a tiny, fuzzy window into something much bigger, much messier, that’s brewing with Gen Z. And frankly, it’s kinda terrifying.

Bonnie Chan, the CEO of the Hong Kong stock exchange, she calls it "new consumption" – emotionally driven purchases. She held up Labubu as her prime example at the Fortune Global Forum. Emotionally driven? Give me a break. Let's be real, it's desperation-driven. You got young urban shoppers, "frustrated by limited career options and social mobility," blowing their cash on "hobbies and small pleasures" instead of, you know, a house. Or a future. This isn't "new consumption"; it's a coping mechanism for a generation that feels like they're being squeezed from every damn angle.

The Blind Box Economy and the Culture Wars

Pop Mart, they're not just selling toys; they're selling a lottery ticket for your soul, wrapped in an adorable, slightly unsettling package. These "blind boxes," where you don't know what you're getting until you open it? That's not innovation; it's a gacha game for real-world objects. It's built to exploit that little dopamine hit, that gambling thrill. Remember those gachapon machines in Japan? This is that, but scaled up, weaponized for social media, and backed by a company that pulled in $1.9 billion in six months. That's not just retail savvy; it's a masterclass in psychological manipulation.

And the irony? Pop Mart’s founder, Wang Ning, he started this whole thing after a stint in tech. So, we've got tech-bro energy applied to collectible toys, designed to hook a generation raised on algorithms and instant gratification. They're making bank, too. Pop Mart's shares surged over 125% this year, making Wang himself worth a cool $18 billion. Meanwhile, the very Gen Z kids fueling that wealth are scrolling through TikTok, joking about climate change making death inevitable before 50. See the disconnect? It's like watching a magic show where the magician gets rich, and the audience just gets poorer, but hey, at least they got a cute monster doll.

What really gets me is this whole idea of "cultural anthropologists" that Ashley Dudarenok, from some consultancy, used to describe Pop Mart. No, they're not anthropologists. They're prospectors, mining the anxieties of a generation and turning it into profit. They identify an "IP," turn it into a "culture moment," then build a "media ecosystem to boost it." That's not studying culture; that's manufacturing it, then selling it back to you. They ain't building culture; they're building a consumer cult.

From Blind Boxes to Street Protests: The Gen Z Reckoning

But here's where it gets interesting, and kinda scary, if you're one of the old guard clinging to power. This same Gen Z that's shelling out for Labubu dolls because they're "frustrated" and looking for "small pleasures" is also the same Gen Z hitting the streets. Hard. We're talking about youthful protestors toppling governments in Madagascar and Nepal this year. Bulgaria's government just pulled its budget after thousands descended on Sofia.

It's not just about cute toys, is it? It’s about a simmering rage. They grew up through Trump, Brexit, COVID, Ukraine, inflation. They've seen the world burn, and they've watched the adults in charge just kinda... shrug. So, when you combine their economic frustration with deeply ingrained anxieties about their future, about the planet, about systemic corruption, you get a powder keg. These protests, they're not organized by old-school political figures. They're born on social media, flash mobs turning into genuine societal upheaval. They're unpredictable, uncontainable. This ain't your grandpa's protest march; it's a digital wildfire.

And how could it be anything else? Think about what Gen Z actually fears about dying. Not death itself, but how they'll die. School shootings, police violence, climate catastrophes. They've watched death stream live, in high definition, since they were kids. It makes sense they're not scared of abstract mortality; they're scared of the specific, horrible ways they might go out, ways often tied to the failures of the systems they've inherited. "Rich people get to die peacefully in their beds," one 20-year-old student told a researcher. "The rest of us get to die in debt or in some mass casualty event." That's not cynicism; that's just a cold, hard read on reality. I asked Boomers, Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z their biggest fear about dying. The answers reveal everything

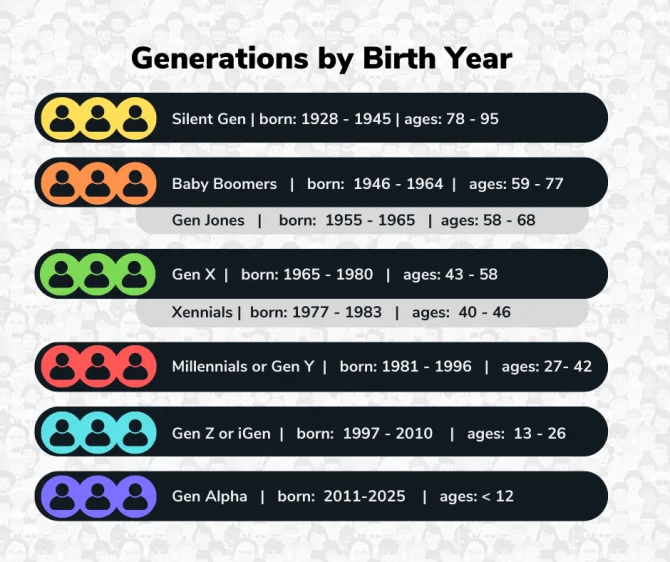

This generation, the ones born roughly between the mid-90s and the early 2010s, they're not just buying different stuff or protesting differently. They're fundamentally re-evaluating everything. They treat death like an old friend because it’s always been lurking. They joke about it, meme about it, because what else can you do when the world you're handed feels like a ticking time bomb? This isn't a generation of dreamers; it's a generation of survivors, trying to find meaning, or at least a cool collectible, in the wreckage.

Then again, maybe I'm overthinking it. Maybe it's just a cute doll. But every time I see one of those Labubus hooked onto a celebrity handbag, I don't see a trend; I see a tiny, grinning monster staring back, a symbol of a generation that's had enough, and honestly... they're just getting started.